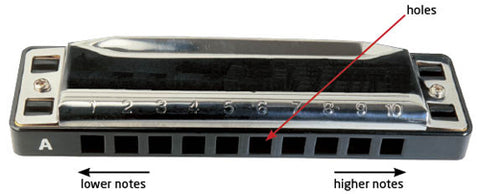

How does the harmonica work? You inhale through it or exhale through it and it makes notes. You change the shape of your mouth, move your tongue around, open and close your throat, breathe with different pressures and attacks, and the notes it makes changes. You do it enough and you figure out what makes what happen.

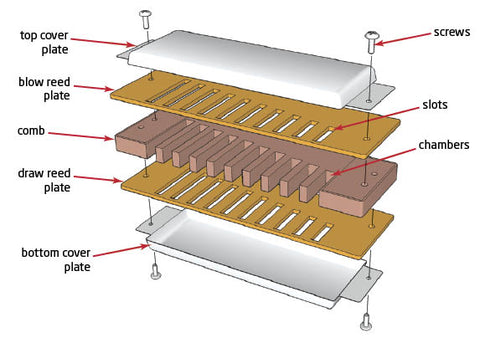

A harmonica consists of two reed plates, the top one for blow reeds and the bottom one for draw reeds, which are attached to a comb and shielded with top and bottom covers. Each reed plate has different length slots over which reeds of corresponding length are fixed at one end. An air stream passes over the reeds into or out of chambers in the comb and causes the reeds to vibrate. This configuration of reeds puts the harmonica in the class of so-called free reed instruments.

The tiny harmonica does not have any resonant body like a guitar or violin, or a sound board like a piano. Nothing in the harp appreciably amplifies its sound or resonates. The resonance comes from the player, which is largely why the harmonica is such a personal instrument. Many people will tell you that the material out of which the body of the harmonica is made determines how it will sound. While there may be very small differences in tone due to materials, any such difference is essentially negligible to all but the most advanced players.

Blowing, Drawing and Bending

Normal blow notes are caused by the upper reeds crossing their slots when the air stream enters through the holes in the comb, flows over the inner reeds, and exits through the slots. The reeds move into their slots, stopping the air stream, and then out the other side of the reed plate, which lets the air flow again. As the reed deflects it gains energy like stretching a spring or a rubber band. When the air pressure is released after the reed passes through its slot the energy in the reed causes it to spring back toward its starting position, once again crossing its slot and cutting off the air stream. This process repeats while the air stream is maintained.

Normal draw notes work similarly but are caused by the lower reeds crossing their slots when the air stream flows over the outer reeds, enters through the slots, and exits through the holes in the comb. This action of the reeds where they first move into their slots is traditionally called a closing note. Bends to change the pitch of closing notes are called closing bends. During normal draw or blow bends, both the draw reed and the blow reed can participate in making the note. As you start with a draw note and bend it down to its limit, initially the draw reed makes the note as above, then both reeds vibrate through their slots to make the note, and finally, at the deepest part of the bend, only the blow reed is making the note. You can verify this by removing the covers and using your fingers to stop the vibration of the upper and lower reeds at various times during a bend.

The reverse happens during blow bends: the blow reed starts, both reeds participate, and finally only the draw reed makes the sound. The range of bending available for a pair of reeds is determined by the pitches of the natural notes of the reeds (i.e. the unbent notes). The pitch can be bend down from the high note to just lower than 1 semitone (one half step, e.g. B to C) above the low note. The opposing reed, i.e. the blow reed during a draw bend, starts by moving away from its slot. This deflection adds energy to the spring that is the reed. When resonance factors are just right the opposing reed can gain enough energy that when it springs back it goes all the way through its slot. The action of the reeds where they first move away from their slots is traditionally called an opening note. The physics of exactly how all this interplay between the reeds, air stream, and slots works is largely unexplored, unintuitive, and not well understood.

The point to understand is that during a normal bend, one reed is operating in a closing note fashion while the opposing reed is operating in an opening note fashion. The closing reed's pitch gets lower while the opening reed's pitch gets higher than their corresponding natural notes.

Overbends, Overdraws and Overblows

During overbends, i.e. overblows and overdraws, the resonances and air flow characteristics are such that the closing reeds don't participate in making the sound, and only the opening note is played. (It is possible to play in such a way that the closing and opening reeds both play and produce different pitches. This is usually caused by poor overblow technique, but can be used to achieve two-note double stops that can't be achieved any other way.)

The action of stopping the closing reed from sounding is often called choking the reed, which forces the closing reed into its slot with very little energy so that it neither crosses its slot nor has enough energy to spring all the way back to its normal position. With the slot blocked the air stream cannot flow that way, and with the little energy in the spring the reed remains in position to block the slot, so the closing reed vibration never takes place.

Overbends are opening notes, so their pitch is higher than the natural note of the reed--just the opposite of normal bends.